“When you are having a really good espresso, which doesn’t happen too often, you know exactly what enjoying an excellent coffee means. For me, it must have a full body, that’s what I call the essence of coffee. That’s why it mustn’t be too watery. Moreover, I love cocoa and dry roasting flavors with a slight but clear tinge of sourness,” Professor Chahan Yeretzian describes his perfect cup of coffee.

Professor Chahan Yeretzian is a Switzerland-based coffee scientist. Yeretzian teaches analytic chemistry, bioanalytic chemistry and diagnostics at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences. Hired by both the private sector and the government, he conducts research on the ins and outs of coffee with his team of experts. For this purpose they have developed methods and instruments that allow them to evaluate not only the subtlest changes in the coffee beans during roasting, but also the exact time at which they occur.

“This is how we can bring out particular flavors,” Yeretzian explains. He drinks six to eight cups of coffee a day, sometimes more for research purposes. Since 2009, Yeretzian has been a board member of the Swiss section of the Specialty Coffee Association of Europe. In 2014 he was elected director of the board while also chairing the association’s research committee. A year later he was elected to the board of the Association for the Science and Information on Coffee. He dedicates all his efforts to stimulating the development of the coffee industry, from the farmers and supplying countries to the end consumers, thus improving the quality of the final product we drink today.

Yeretzian received his doctoral degree in chemistry from the Swiss University of Bern, and, after being awarded a scholarship, relocated to California, where he conducted research at UCLA for three years. He went on to receive the Alexander-von-Humboldt Junior Award and moved Germany, where he continued his research at the Technical University of Munich for two more years. In 1996 he returned to Switzerland to work at the Lausanne-based Nestlé Research Center, where he devotes his time to researching coffee.

| Chahan Yeretzian with his parents and Aïda Kegham Yeretzian in Lebanon, 1966 |

Worst student becomes best

Chahan Yeretzian was born in Aleppo, Syria in 1960. He disliked school as a child, but embarked on a brilliant academic career as an adult. He was seven years old when his father made the decision to leave Syria. By 1967, tensions in the region had escalated, eventually resulting in what became known as the “Six-Day War” between Israel and its Arabic neighbors. Every high-ranking official in Syria was drafted, including Chahan’s father, who had nothing to do with the military. “One day an officer’s uniform was sent to his home, which immediately prompted him to say that it was time to leave,” Chahan remembers.

Chahan’s father maintained good relations with international organizations and was offered the chance to work for one of them in Switzerland, an offer he readily accepted. “At the beginning I hardly spoke a word of the foreign language and couldn’t keep up in class at all. And I wasn’t very interested anyway,” Chahan recalls. For the next three years, he was the worst student of his class. “Like in any other Armenian family, education was of great importance in ours. My mother began doing my homework with me.”

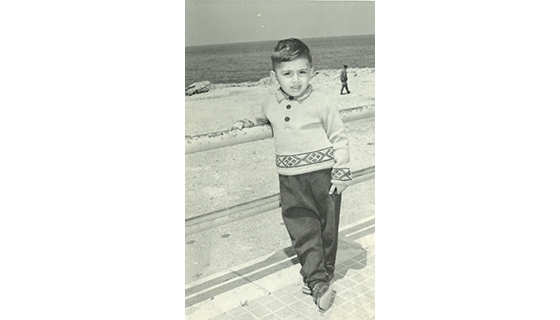

| Chahan Yeretzian before his departure to Switzerland, Beirut, 1964 |

From that time on he was among the top students in class and made a lot of friends. “My parents never failed to emphasize the importance of being good at what you do,” says Chahan, who also succeeded as an athlete and made the Swiss National Volleyball League B team. “For my father it was very important that I always be the best at what I was doing,” Chahan adds. “My father Kegham had a very difficult childhood: he was poor and had to work after school when he turned 17 to support his mother and little brother. Despite those circumstances he was always at the top of his class and went on to study law and politics. Once he had his diploma he took up a job with the Syrian Railroads branch in Aleppo at the age of 23, working his way up to the position of manager of the Syrian Railroads while being in charge of the Aleppo branch of the Armenian General Benevolent Union. Never politically active, he was an extremely conscientious person, very honest, straightforward and strict. After moving to Switzerland, he founded the Swiss section of ‘Himnadram’ in 1989.”

| Chahan Yeretzian’s grandparents Linda Meymarian and Dikran Yeretzian at their wedding,1923 |

Kegham Yeretzian lost his father at the age of 15. His mother, Linda Meymarian, an Armenian Genocide survivor, remarried, but the stepfather never really became part of the family. “I never met my grandfather Dikran Yeretzian, who was born in Sasoon and was the only family member to survive the deportations. Even before they started, his brother David was caught and killed by the Turks while on a mission as a messenger to bring help for their encircled home town,” Chahan says. After some time had passed, his grandfather Dikran opened a pharmacy in Aleppo, which he was forced to sell a few years later. “My grandmother Linda was a very gentle person. She was born in Adana in 1907. When the Genocide began, the Meymarian family moved away in time and traveled to Aleppo, where they built a new life. The Meymarians were a relatively large family who owned land and houses in Adana.”

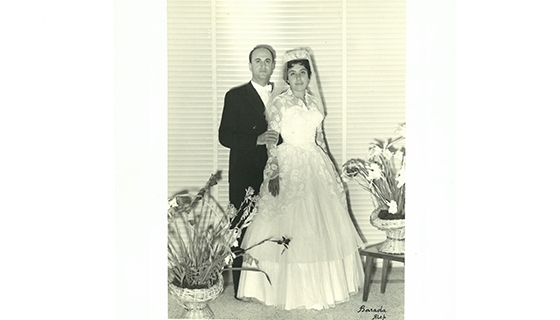

| Kegham Yeretzian and Aïda Papazian at their wedding, 1957 |

Match made in a newspaper

“My father read in the paper that my mother, 18 years of age at that time, had graduated high school in Beirut at the top of her class. He wrote the family, asking to be formally introduced. Once invited, he traveled to Beirut for a visit to propose to her,” Chahan recalls. Chahan’s mother Aïda came from a highly respected family that had left Istanbul before the Genocide.

| Aïda Papazian’s father Kevork Papazian |

“It was mainly our mother who raised us,” Chahan says. “My father kept to a tight daily schedule. He was a very responsible man and set an example for us kids,” Chahan notes, adding that his mother, who felt far away from Armenia in Switzerland, had regularly gone to cultural festivities and attached great importance to her children learning Armenian. “And yet I don’t feel exclusively Armenian. When asked what I am, I’d always say Armenian first, but with a Swiss way of thinking. Our Armenian history is, of course, quite different from that of the Swiss. However well I may know Swiss history, mine will always be that of the Armenians,” the professor believes. He especially appreciates the Armenian understanding of family: “You are part of a large family and share everything.”

Yeretzian is convinced that Armenians should not get entirely lost in their struggle to get the massacres recognized as Genocide. He agrees that it is important for world history, Europe and Turkey, whose continued denial of this key event inhibits the country’s further development. “For me, however, all this belongs in the past,” Chahan says resolutely. “As a new generation of Armenians, it’s our duty to look ahead and shape the world in which we live today.”

Chahan Yeretzian is married to Carla Kapikian, an American-born woman from New York of Armenian descent. The couple has two children, Liana and Michael.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.