Dr. Yervant Zorian is the chief architect of Synopsys Inc., a company that has approximately 10,200 employees worldwide. He is also president of its Armenian subsidiary, which employs 700 people. The company was founded in 1986 and grosses $2.2 billion today. It develops semiconductor design software as well as predesigned blocks and design-for-manufacturability solutions, such as self-test and self-repair blocks for semiconductor chips.

“Today’s semiconductor manufacturing is very precise, but not perfect. As a result, most chips are manufactured with defects in them,” says Dr. Zorian. “This is why we create intelligent engines that allow a chip to test and repair itself. These engines are embedded in the chip design and are automatically launched each time you turn on an electronics system, whether it is a smart phone, car or laptop.”

Over the past 30 years Dr. Zorian has introduced and spearheaded this innovative technology, becoming a world-leading authority in self-repairing electronic systems. Today, he holds 35 U.S. patents and boasts 350 scientific publications and four books on this topic. The EE Times ranked him among the top 13 influencers in the semiconductor industry. He was recently awarded Armenia’s National Medal for Science.

| Yervant Zorian with his team of the Synopsis branch in Armenia , 2014 |

Dr. Yervant Zorian has also made a significant contribution to the development of Armenia’s IT sector. He was among the first to discover the country’s IT potential in the early 1990s and to open it up to foreign companies. “The Armenian nation and its prosperity have always been important to me,” says the Aleppo-born scientist. “As a child, I saw how my parents and grandparents tirelessly volunteered for the Armenian community. From a young age their examples taught me to serve our nation with my knowledge and expertise.” That’s why Dr. Zorian decided that he could use his profession as a way of helping Armenians early in his career.

“After Armenia achieved independence in 1991, I came to the country to meet people from my line of work. Armen Sargsyan, who later became prime minister, introduced me to highly skilled IT professionals from the Academy of Sciences and the Mergelyan Institute, and we began to build bridges,” he says.

| Yervant Zorian with his wife Rita and the Catholicos of All Armenians Vazgen I, Echmiadzin, 1986 |

Due to the economic crisis of the early 1990s many IT experts were deciding to leave the country. In order to reverse this “brain drain” Dr. Zorian secured funding from the President of the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU), Mrs. Louise Simone, and assembled a small team in the country. “At first, we established a lab for a group of 20 experts at the American University of Armenia,” he remembers. By that time, Zorian had completed his Ph.D. in Canada and was working in Princeton, New Jersey, for AT&T Bell Laboratories, a leading research institute. He visited Armenia regularly and gave seminars on a range of IT topics for that expert group. “After two years, they were ready to take over a number of research projects from AT&T, thus earning their first foreign contract,” Dr. Zorian says proudly. After that, other countries took an interest in entering Armenia’s IT market. Dr. Zorian introduced them to the highly qualified IT experts available and guided their growth from small teams of four or five people into the large companies that make up Armenia’s IT and research sector today.

At present Dr. Zorian is involved in several initiatives to ensure the prosperity of the IT sector in Armenia and promote technological education among young Armenians. In his view, a professional education is a powerful weapon. Indeed, for his forefathers, it served not only as a path to success, but literally as a means of survival.

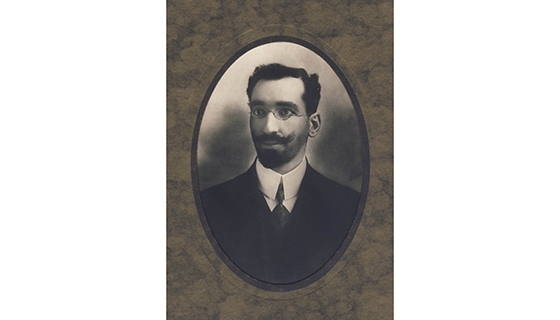

| Yervant Zorian’s grandfather following graduation from the American Anatolia College in Marsovan |

Education saves lives

Dr. Zorian is named after his paternal grandfather Yervant (1882-1954). Yervant was the younger son of Haroutune Zorian, a prominent merchant from Trabzon. Holding highly progressive values for his time, Haroutune ensured that his two sons, Apik and Yervant, both received university educations. He lived to see his elder son Apik become a lawyer, but was killed by Hamidiye units on the orders of Abdul Hamid II in 1895 before he could see what his younger son, Yervant, would accomplish.

Haroutune had sent his family away from Trabzon before the massacres, but returned to guard their property himself. “When the family returned, he was no longer there, and the properties had all been plundered. They had to start over,” Dr. Zorian says. His grandfather Yervant was only 12 years old at the time. “Twenty years later, when the Armenian Genocide began, my grandfather had already graduated from the American Anatolia College in Marsovan and moved to Beirut to continue his studies in commerce at the French University. His family’s decision to continue his education in Beirut saved his life.”

| Yervant Zorian’s grandfather (far left) on the board of AGBU, Aleppo, 1920 |

Yervant senior became the chief accountant and treasurer of the State of Aleppo in the 1920s and worked till he retired in 1943. He was strongly committed to the Armenian community, particularly to young Armenians. His position enabled him to offer employment to many of his compatriots. “Unfortunately, I didn’t know him personally. He died before I was born. However, people often spoke of him and referred to him,” says Yervant. For 25 years, his grandfather held prominent positions in the AGBU, and in 1931 he founded the AGBU Armenian Youth Association, which continued to advocate for education and professional training among Armenian youth. In 1946-1947, he played a key role in efforts to repatriate people to then-Soviet Armenia.

| Ashdod Zorian paints the portrait of famous Armenian poet Silva Kaputikian |

Apik, however, did not have the same fortune. He remained in Trabzon where he was abducted by Ottoman soldiers before his wife and three children were forced on a death march through the mountains of Anatolia. Along the way, the mother entrusted two of her children to a Turkish peasant and, in doing so, saved their lives. Her son, Ashod Zorian, later became a renowned painter. After the atrocities of 1915, he and his sister were taken in by their cousin and her Iraqi husband, an army officer, who passed them off as Arab relatives. His boarding school in Constantinople nurtured Ashod’s artistic talent and won scholarships to study at fine arts institutes in Vienna and Rome. In 1929 he moved to Egypt, where he worked in Armenian schools and began to teach in his own studio. “Even the wife of the King of Egypt is said to have studied painting under him,” says Dr. Zorian. “This is also where he painted the portraits of numerous celebrities when they visited Cairo.” Using his Nansen passport, Ashod would regularly visit his uncle Yervant and his family in Aleppo. “I remember he would often play with me and my sisters, but he never married and never had children of his own. His memories of his childhood years always seemed to haunt him,” Yervant remembers.

| Yervant Zorian’s maternal grandfather Aram Minassian and his wife Arpine, Aleppo, 1927 |

On the other side of the family, Dr. Zorian’s maternal grandfather Aram Minassian did not have to struggle through the atrocities of the Genocide. His family had been merchants based in Aleppo for centuries without ever hiding their identity. “When the Armenian refugees reached Syria, it was Aram’s father, Garabed, one of the community leaders in the Armenian Apostolic Church, who helped organize the relief committee to support those who had survived, providing health care, education and employment for them,” says Yervant. Following his father’s example, Aram Minassian returned from his studies in Berlin and continued serving the newly expanded Armenian community. Later, he chaired the AGBU District of Syria from 1953 to 1967. During this period, he helped establish the AGBU high school in Aleppo and oversaw its growth.

| Apik and Hilda Zorian with their children Yervant, Maida and Houri, Aleppo, 1968 |

Dr. Zorian’s parents, Apik and Hilda, continued the family’s tradition of serving the Armenian community in Aleppo, especially in education. After studying engineering at St. Joseph University in Beirut, Apik spent 30 years as technical director of the Electricity and Water Company in Aleppo. In his free time, in addition to leading the AGBU education committee of Syria, Apik researched Armenian architecture and fine arts and published three award-winning books on the impact of Armenian culture.

| Yervant Zorian lectures in the computer classroom of the AGBU school in Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010 |

This ensured that Dr. Zorian’s Armenian identity and heritage became an essential part of his life from a young age. In Aleppo, he attended the AGBU high school and became committed to its students’ society. He continued his graduate studies in Los Angeles and Montreal, where his future wife, Rita Chadarevian, was attending medical school. Eventually, they settled down in Silicon Valley, where Yervant established the Silicon Valley branch of AGBU, and in 2006 founded the AGBU Armenian Virtual College (AVC), which provides Armenians worldwide with the opportunity to connect with their identity by studying Armenia’s history, culture and language online.

“We all need to give back to our nation, especially to its next generation, for the wealth that we inherited. Every Armenian can find a way to foster the prosperity of this nation by leveraging his or her know-how. As a worker in the technology domain, I concentrated on advocating for the IT sector in Armenia and offering Armenian knowledge via technology,” Yervant says proudly adding: “As a result, today the world’s premier self-repair technology is produced in Armenia by our team at Synopsys, and, so far, over 16,000 online learners around the world benefited from Armenian Virtual College courses and e-books. For generations, my family was fortunate enough to be able to use education as a weapon in the most challenging circumstances; through my work, I simply hope to extend the same opportunity to the next generation of Armenians.”