Born in Gyumri, Armenia in 1987, composer, singer and musician Tigran Hamasyan is as comfortable with jazz as he is with Armenian folk music. Only three years after he began playing piano, he won the Montreux Jazz Festival’s piano competition at the age of 16. He released his debut album at the age of 18, after moving to Los Angeles with his family. He later returned to Armenia, where he taught master classes and found inspiration in his beloved Armenian music.

Tigran’s ancestors were from Kars. His great grandfather, Alexan Hayrapetyan, was from the Bashkadiklar village, and his great grandmother, Hripsime (Horomsim) Alexanyan, was from Pilvari. Records of the Parish Register of Bashkadiklar, preserved in the Armenian National Archives, document the November 28, 1902 marriage between 21-year-old Alexan and 19-year-old Hripsime, as well as the June 1, 1907 birth of their first child, Tsolak.

| The Parish Register of the Bashkadiklar village in Kars, dated 1907. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Armenia. |

When her husband Alexan was killed in the Genocide, Hripsime was left alone with her three children. It is not known how, but in 1917-1918 they managed to flee from Kars to Alexandropol (now Gyumri), taking the orphaned children of her brother and brother-in-law with them.

“She never told us any details; she would just sing and cry. I can only recall one episode when she talked about the children starving as they hid for safety during their escape, and how she had to climb over corpses to find nourishment for her children,” recounts Tigran’s grandmother Melanya Tsolaki Hayrapetyan.

Thirty five-year-old Hripsime was unable to take care of the eight children in her custody and had to take her youngest daughter Salat to an orphanage in Alexandropol. Shortly after, Salat died in the orphanage. “Now I wonder how she was able to send her own child to an orphanage and take care of her brother’s and brother-in-law’s kids. She was grief-stricken, deep in her soul, and would always wear black. Later, one of her sons went to war and never returned and, after the death of my mother, my grandmother took care of my youngest brother as well,” Tigran’s grandmother Melanya remembers.

Hripsime Alexanyan kept herself busy with the upbringing of her grandchildren. She had no formal education, but she was a great expert on folklore. “Numerous fables, parables, rhymes and fairy-tales – she recited them all. She nurtured us, her grandchildren. I don’t even remember the time spent with my mother because it was my granny who took care of us and raised us,” says Melanya.

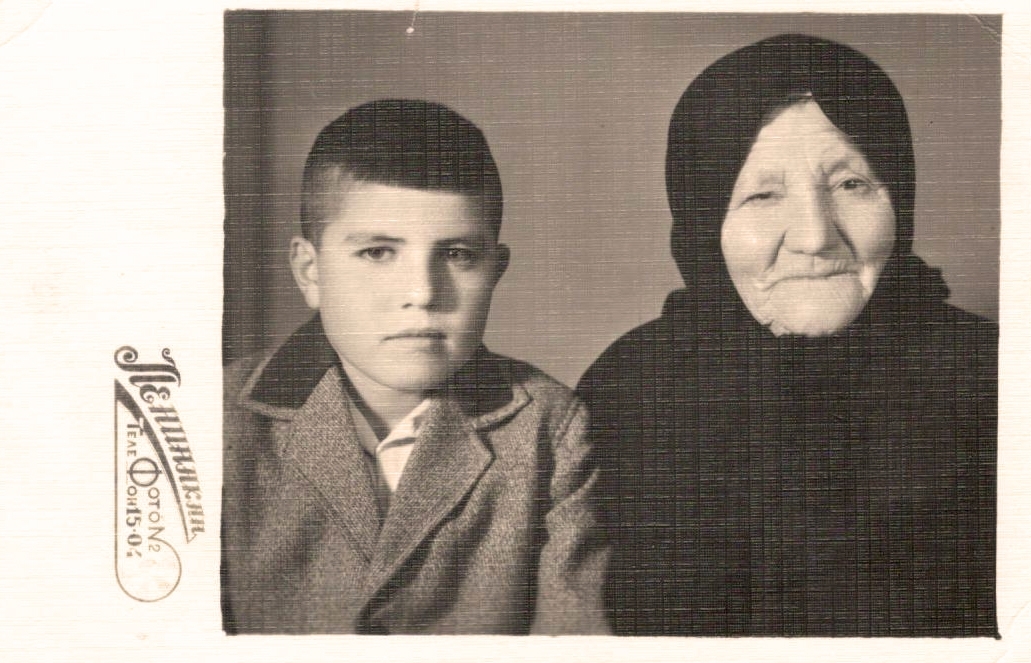

| Genocide survivor Hripsime Alexanyan and her grandson Rafik |

Tigran’s other great-grandmother, Anzhela Oltetsyan, was also from Kars. During the massacres, her entire family was slaughtered in front of her eyes; only she and her two sisters managed to escape.

“My mother-in-law, with her two sisters, ended up in Polygon, one of the Near East Relief orphanages operating in Alexandropol. The two sisters were sent to the United States from that orphanage and Anzhela was later adopted by her uncle, who had given her his Bisharyan surname,” says Melanya.

| Genocide survivor Anzhela Oltetsyan with her husband and children |

Although the Oltetsyan sisters sent inquiries in search of Anzhela, the fear and secrecy of the Soviet years prevented them from finding her.

Tigran Hamasyan doesn’t know much about the history of his ancestors who survived the Genocide. “My grandmother says that my great grandmother Hripsime would sing ‘Krounk’ and cry when she was alone; she would never take the black scarf off her head. My other grandmother, Anzhela, would never know that her sisters kept searching for her.”

Tigran’s recently released album “Tsaghrarmat” (“Mockroot”) differs from his previous works as it embraces much of his own history. “Yasaman” (“Lilac”) is about a tree in the yard of his childhood home; “Song for Melan and Rafik” is dedicated to his grandmother and grandfather; “Kars 1” and “Kars 2 Wounds of the Centuries” is about his maternal grandparents’ ancestral home.

This is my attempt to look into myself, to get to know myself, to comprehend my roots. We have to be close to nature – try to understand ourselves, our essence – for nature always wins over human complexity. This album is a kind of longing and nostalgia for a human nature that’s more spiritual, more loving, more together with its roots. It encompasses a sort of sacrifice within itself, a sacrifice for the sake of human inspiration,” says the 28-year-old master of folklore improvisations.

Tigran and the Yerevan State Chamber Choir, led by Harutyun Topikyan, joined forces to present 100 concerts dedicated to the Centennial of the Armenian Genocide. Titled “Luys i Luso,” the concerts give new interpretations to spiritual music from the 5th to the 19th centuries. The performances, which began in Yerevan on March 24, 2015, toured Europe, the United States, Russia and Turkey.

| Tigran Hamasyan © PAN Photo / Vahan Stepanyan |

“I desperately wish our spiritual music could be played in the Saint Apostles Church in Kars, but it is not possible as the church has been turned into a mosque. Still, we had a concert in today’s Turkey,” says Tigran. He hopes that someday, his dream will come true.

Cover photo: Tigran Hamasyan and his grandmother, Melanya Tsolaki Hayrapetyan. © PAN Photo / Vahan Stepanyan

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.