Bisi Ideraabdullah and her Imani House empower people in Brooklyn and Liberia, helping marginalized youth, families, and immigrants create vibrant neighborhoods where residents are the decision-makers who take responsibility for the improvement of their lives and surroundings. She believes that anyone can succeed if they are motivated and have access to relevant skills, information and opportunities.

Imani was meant to be the name of her daughter, but it ended up being the name of the organization, which became her life’s work. Bisi Ideraabdullah, co-founder (together with her husband) and executive director of the Imani House, remembers the day she lost her child. It was back in 1982, in Charleston, South Carolina, when she and her husband were on vacation. The happy family of Bisi and Mahmoud was expecting then. Bisi went into labor early, and her husband took her to the nearest hospital.

“We didn’t know that it was a private hospital. There was a white woman. She asked for insurance, we didn’t have it, and she turned us away. But when you are in labor, they are supposed to admit you, and she knew I was in labor. The girl that was with her said: “We can send her to another hospital in a wheelchair.” And the woman was really angry. Her face distorted and she said: “No, she can walk.” Actually, I could not walk, I should not be walking. I was in so much pain. By the time we got to another hospital, we lost the child. It wasn’t a medical decision she made; it was a racial decision. It was a shock for me. I was very angry and disappointed with the United States.” That was the first time Mrs. Ideraabdullah faced racism up close and personal, and that was the moment that she made the final decision to move to Liberia, West Africa.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, Bisi Ideraabdullah had been to Africa before. In 1973, at the height of the “Back to Africa” movement, she received a scholarship from the Brooklyn College and went to Ghana for a year. After returning to the US, she always wanted to come back to Africa and live her life there. “I wanted to be somewhere where my children could grow up without being second-class citizens,” she explains.

In 1985, Bisi Ideraabdullah, her husband, and their 5 children moved to Liberia. This was a deliberate choice and they were full of hope and expectations as Liberia meant “the land of the free,” founded by African people who had been enslaved in the United States. Bisi Ideraabdullah describes the first 5 years of life in Liberia as “utopia.” But then, the first civil war broke out there, and in 1990, they had to send the children back to the US to be with the relatives for a while. “We sent the children to my mother, but I convinced my husband to stay. I said: “This is our home, and I don’t want to leave. I want to be here, when the war ends, to help to clean up.” We didn’t have an idea that it was going to go on and on. It just didn’t end, it got worse. It was all an ethnic cleansing. They were just going to different areas and slaughtering people. It was not the Liberians I knew. I don’t know what turned them into monsters.”

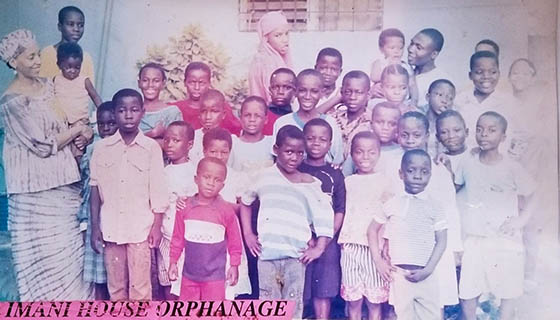

The first civil war in Liberia lasted till 1997, claiming lives of more than 200,000 Liberians and putting a million others into refugee camps. Being a teacher and a businesswoman without medical background, Auntie Bisi or Sister Bisi, as people called her, started volunteering at the local hospital near their home, caring for the wounded and sick. A large number of abandoned children were brought there for treatment and many of them were never claimed after recovery, so she opened a makeshift orphanage in her own home.

“It was extremely risky. The clinic that I went to volunteer was led by the warlord Prince Johnson. Once, he came there with tanks and said that rebels were in the clinic, the rebels against his soldiers. He got all of us out of the clinic. We were standing there and trembling, without knowing what to expect as he was drunk.”

As an American, it was easier for Bisi Ideraabdullah to gain access to international organizations and get a chance to have a closer look at how they were spending money. As a local, she knew better where the real need was to be met. “I went to the UN and ask them for a tent. Then I went and got the people who volunteered with me at the hospital. I said: “Can you join me? We are going to open a tent to serve the displaced people in the camp.” We opened that tent and served those people. Then I went to the next level and I said: “We are going to build a clinic on our land.” That was in 1993.”

At some point, she had received a grant from the UN to build small chicken coups to provide supplies to the displaced people. Part of the project included construction training for men and ex-combatants, and that gave Bisi Ideraabdullah an idea. Using mud blocks and cement, the trainees built a similar structure on her land, and she turned it into a clinic to serve thousands of people from Liberia and Sierra Leone forced by war to flee their homes: “It had a roof [and] chicken wire around. We divided it into rooms. Chicken never lived in it. And we had a clinic. From there, we began to do public health. I just felt so needed and useful to the community. And I was able to do things that one would say: “You can’t do.” I learnt, and I think that’s what people who care enough do – they learn.”

During the civil war and in its aftermath, the Imani House has served those in need, regardless of their ethnic tribal groups or religious background. The clinic grew and eventually became a full-service facility catering to the needs of thousands of Liberians, mainly women and children. In addition to the healthcare services, the Imani House has also launched an adult education program, as building women's literacy skills and self-reliance is at the core of the Imani House’s mission.

“The clinic belongs to Liberians who are there. Over the last 28 years, many of these people that have been with me have taken on the role of social justice as well. They understand human rights. They are all from different tribes and they are not allowed to disparage any other tribe, any other ethnic group. And they become just models of what I would hope one day Liberia will be. We have educated people who are going to college now, and they started from zero; they didn’t read at all.”

Her activism came with a cost – her family and the clinic were attacked many times. In 2003, a rebel group kidnapped four of her staff; it took 6 months to set them free. Despite living through a war and risking her life, Bisi Ideraabdullah never regretted her decision to move to Liberia. She is still facing many difficulties there. Most of the land that the Ideraabdullah couple purchased to build community centers and other facilities has been taken away from them. She has all the rights to it, but the corruption is too widespread in Liberia, and speaking up can be dangerous.

The hurdles she faced never broke her spirit. They made her stronger and motivated her to work harder, serving and educating people: “My mission is to help people build sustainable communities where they can be the decision-makers. This is very important. I have always been proactive, and I have always had the feeling that we should inspire others.”

The Imani House clinic was a real salvation during the Ebola outbreak in 2014. They lost two of their staff, but were determined to remain open, even without the proper protective gear: “We purchased rain suits as hazmats and construction masks [Bisi Ideraabdullah laughs]. But that’s the kind of creativity that the Imani House has lived by.” And that experience with Ebola helped them to be more prepared for COVID-19.

Traveling back and forth between Liberia and the United States to raise international awareness of the civil war crisis, Bisi Ideraabdullah witnessed many similarities between the struggles of people in Liberia and the less fortunate residents of her native Brooklyn. She came up with the idea to launch a program there as well. The Imani House’s first US project started in 1991 with the establishment of the community center to help those with low literacy levels, mainly immigrants.

Since 1990s, the Imani House’s programs have expanded to meet the diverse and growing needs of the Brooklyn and Liberian communities. In the US, they directly serve over 1,200 low-income families, youth, immigrants and elderly each year, offering Afterschool Program, Summer Camp and Adult Education programming. Indirectly through referrals, community outreach, workshops and forums, they serve an additional 4,000 persons. In Liberia, the Imani House’s Maternal and Child Health Care Clinic, Adult Education program, Women’s Health Manual Project and High-School Peer Education services benefit over 14,000 Liberians annually.

“What motivates me? I just cannot stand injustice. And what happens in the world is that the minority in our world is ruling the whole world. The minority in our world is dumbing down education so that poor people remain poor,” says Bisi Ideraabdullah.