At first, it was just a voice – pure and profound, echoing a lost Levant. A voice from the depths of a Damascus night, accompanied by a few notes on the piano, a bit of percussion, a wavering saxophone. That was the sound of her two albums, “Hal Asmar Ellon” and “Shamat,” with Oriental jazz that stirred hearts in the East and West alike.

In 2011, the conflict in Syria was a terrible blow for Lena Chamamyan. In response, she carried her creative energy and the sufferings of her people to Paris, that other capital of Arab culture. Here, as both an Armenian and a Syrian, she lives in a dual diaspora. Her exile finds a voice in her latest album, “Ghazl El Banat,” a collection of her songs of peace and calls to protect the women and children of the world.

Today Lena Chamamyan is one of the few female artists from the Middle East who is able to write, play and interpret her own works. While she draws on the rich Syrian classical and folk repertoire, her Armenian roots are also ever-present – her interpretations of traditional songs such as Komitas’ “Sareri Hovin Mernem” form a regular part of her performances, drawing applause from her fans in Armenia and throughout the diaspora.

In her Parisian refuge, Lena is still smiling. Although she is far from Damascus and her parents, she has found a new musical niche in “the city of lights,” a new audience and new links with artists from diverse backgrounds. These include André Manoukian, with whom she is preparing her latest album.

André Manoukian and Lena Chamamyan © DR

A child of Syria’s cultural mosaic

Lena was born in the Syrian capital in 1980. Her father, Artine, is an Armenian from Aleppo, her mother, Ghada – a Syriac from Mardin, a city in the southeast of what is now Turkey. Lena’s genes have a heritage that dates back thousands of years to two ancient peoples, now extinct, of the Ottoman Empire – two peoples united by faith and martyrdom.

Sarkis Chamamyan, Lena’s great-grandfather on her father’s side, was from Marash in Cilicia, present-day Kahramanmaras in southern Turkey. Born into an Armenian Catholic family, he became a calligrapher. “His education saved his and his family’s life in 1915, because, by sparing him, the Ottoman army could use him to write military communiqués,” Lena says. At the end of the war, they came to Aleppo, where a large colony of Armenians previously deported from Cilicia had settled. Sarkis died there soon after, never able to return to his native land.

His son Hovannes, Lena’s grandfather, was a tailor in Aleppo. His Marxist sympathies and involvement with the Syrian Communist Party in 1945 caused him many problems. Lena wonders how someone could be both a Marxist and a Christian – it can only be explained as part of the complexity of the Armenian soul. Unlike many of his comrades, Hovannes chose not to heed the calls to repatriate to Soviet Armenia in 1947 and preferred to stay in Aleppo. In the 1960s the Damascus regime cracked down on political dissidents and he was arrested. His possessions were confiscated and he spent many years behind bars. As a result, his children left Syria and emigrated to Canada. The only one to remain was Artine, Lena’s father. He got a solid education in a Christian school in Aleppo and won a state scholarship to study engineering in Damascus. There he met his future wife Ghada, the daughter of his landlord. The couple were married in 1977. Coming from a mixed family background, Lena’s childhood was not spent in an isolated Armenian community.

Chamamyan family in the 1960s © Photo courtesy of Lena Chamamyan

Lena owes her musical education to the family’s two music lovers – her grandmother Arax Djamidjian, who introduced her to classical singing and traditional music, and especially to her father, a saxophonist who shared his love of the Armenian language and its music. “He still speaks to me in Armenian!” Lena says. But little Lena had a hard time finding her place in the Armenian Catholic school in the old city of Damascus.

“We were divided into three groups: the Armenians, the Christian Arabs and the Muslim Arabs. As for me, I was considered half-Armenian!” she recalls.

Although isolated from her father’s community, she began singing in the Armenian church. “In winter I sang in the Armenian church and in summer in the Syrian church. Today, when they ask me about my identity, I answer ‘Songs, words, and dreams’.”

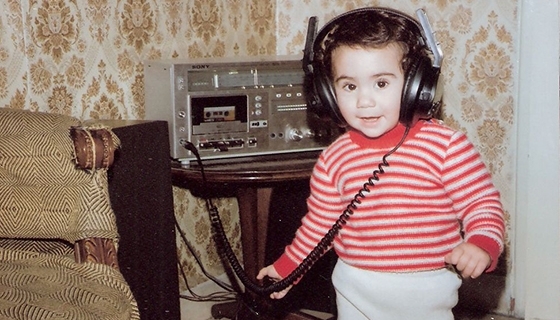

Little Lena © Lena Chamamyan

Between tradition and modernity

Lena began studying music theory at the age of nine and her first instrument was the xylophone. Later on, after studying finance management at the University of Damascus, she entered the State Music Conservatory where she studied classical singing. Although the majority of her music teachers were Russian, her singing teacher, Arax Chekidjian, was Armenian. Lena’s voice – a lyric soprano, very rare in the Arab world – soon set her apart from other singers.

At the Damascus conservatory Lena met talented young jazz musicians. New sounds were born of these meetings: piano, saxophone, percussion, kanoun (a type of Arabic zither) and other instruments. Along with musicians from the conservatory, she travelled throughout the Syrian countryside exploring a musical project that combined jazz influences with her own Arab-Armenian musical heritage. The aim was to express the soul of the Oriental tradition through jazz. Recognition first came in 2006, when Lena won the Al Mawred El Thaqafi prize in Cairo, which formed part of the final round of Radio Monte Carlo’s first Middle East Music Award. With the prize money they recorded a debut album, “Hal Asmar el Lon,” which quickly became a success thanks largely to strong word-of-mouth support.

An Ottoman singer

When Lena discovered Turkey, it once again triggered something new. The story began when she shared the stage with Kemal Arslan, a Turkish musician who traveled to Damascus to perform with her. This was not easy for Lena, who had grown up with the memory of the Genocide. “At first, knowing he was Turkish, I refused to shake his hand. Only little by little did I get to know and appreciate him and since then he’s become a very good friend.” Thanks to Kemal, she rediscovered a whole new side to her family history that had been hidden in the depths of the past. That journey led her to Istanbul, a city where she found a strangely disquieting familiarity. She sang there in memory of the journalist Hrant Dink, who was assassinated in 2007.

In different places and through different projects Lena has also got closer to her Armenian roots. In 2014 she was a member of the jury for the “Tsovits Tsov” international competition of Armenian songs in Moscow, where she met Arto Tuncboyadjian. Later, in Paris, the renowned jazz musician André Manoukian invited her to work with him. The two artists commemorated the centennial of the Armenian Genocide with an interpretation of “Black Sky,” a poem by Hovannes Toumanian. Lena sang it in Armenian.

Lena remains close to her roots, carrying a nostalgia for the sweetness of Damascan life that endears her to the Syrian diaspora. Although she doesn’t have the same fame as the biggest stars of the Arab music world, she values her independence as much as her close relationship with her fans. As war rages in her home on the other end of the Mediterranean, Lena’s voice rings out in protest against suffering, now and always.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.