Bohjalian is emphatic in his belief that the stories Armenians have lost are a vital part of the Genocide’s legacy, for they too carry within them our history and our past.Chris Bohjalian's novels have sold millions of copies worldwide. His stories often take a real-world incident, historical event or “fait divers” as a starting point, from which he weaves intricate and emotionally laden tales that are gripping both for their human aspect and the moral conundra that they present. In “The Sandcastle Girls” he looks back at the Armenian Genocide and asks how such horrifying events are possible, and even more remarkably, how victims survived to form families of their own and thrive in countries near and far.

|

Chris Bohjalian’s book, “The Sandcastle Girls.”

|

A prolific author

Altogether Bohjalian is the author of 18 books and his works have been translated into over 30 languages and made into movies on three occasions. His novel “Midwives” was a number one New York Times bestseller, a selection of Oprah's Book Club and a New England Booksellers Association Discovery pick. His most recent novel, “Close Your Eyes, Hold Hands,” was published in July 2014. His next novel, “The Guest Room,” is due out in January 2016 and has critical scenes set in Yerevan and Gyumri.

Since publishing “The Sandcastle Girls,” Bohjalian has been actively involved in educating people around the world about the Armenian Genocide through lectures, articles and public appearances, which led to his receiving the ANCA Freedom Award. He was also the recipient of the ANCA Arts and Letters Award and Russia’s Soglasie (Concord) Award for “The Sandcastle Girls,” as well as the Saint Mesrob Mashtots Medal, the New England Book Award and the Anahid Literary Award.

A native New Yorker, Chris graduated Phi Beta Kappa and Summa Cum Laude from Amherst College and currently lives in Vermont with his wife, photographer Victoria Blewer. They have one daughter, Grace Experience, who is an actress in New York City.

Before 1915: the Genocide and Abdul Hamid

When most people think of the Armenian Genocide, they imagine a period in history that stretches roughly from April 24, 1915, when Armenian intellectuals were rounded up in Constantinople, taken by boat and train to concentration camps in Ayash and Chankiri and eventually gruesomely murdered, and ends in 1923 with the founding of the modern Republic of Turkey. But widespread massacres of Armenians — pogroms or “chart,” as they are referred to in Armenian — began long before that. From 1894 to 1896, for example, during the Hamidian Massacres alone some 300,000 Armenians were killed on the orders of Sultan Abdul Hamid, earning him the moniker “the Bloody Sultan.”

From Kayseri and Ankara: Two families, a horse stable and a troubadour tailor

Chris Bohjalian’s family history intersects with these terrible events in ways both sad and enlightening. The Bohjalian clan hails from Kayseri, a heavily Armenian city in Central Anatolia. While some of Bohjalian’s ancestors were successful merchants, others also had a decided flair for the literary. If you believe that literature is “in the bones” and that there is some type of literary DNA that gets passed on from one generation to the next, then Bohjalian may owe part of his success as a writer to an ancestor long gone – his great-grandfather Nazaret.

|

Bohjalian’s great-grandfather Nazaret.

|

As Bohjalian recounts in an April 21 publication in Newsweek Magazine titled “The Souls and Stories that Perished in the Armenian Genocide,” the “Aghet” (as the disaster is called in Armenian) did more than just kill people — it also destroyed their stories, family histories and other tales that were passed down from generation to generation.

Countless oral histories, written records and literary tales came to an abrupt end along with the killings.

Chris’ great-grandfather Nazaret was said to have been a tailor who on occasion may also have dabbled in writing. Yet some 20 years ago, when Chris’s aunt Rose Mary handed him an old volume of an encyclopedia on Kayseri Armenians, Bohjalian was in for quite a surprise. He turned to his friend Khachig Mouradian to translate the entries.

|

A page from the encyclopedia on Kayseri Armenians.

|

It turns out that Nazaret was much more than a simple tailor or occasional poet. Bohjalian’s great-grandfather was, in fact, an accomplished bard, a poet troubadour who sang volumes of poetry reminiscent of Walt Whitman, the great American bard of nature. At 14, Nazaret was brought to Jerusalem to perform, something he continued to do throughout his 20s in Constantinople before returning to Kayseri to start a family. Troubadours, or “ashougs,” were an integral part of Armenian and Anatolian life at the time. In Kayseri, he continued to write in his former vein — until 1895, that is — when his writing turned decidedly grim. The massacres that Abdul Hamid had instigated elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire had reached his home town in November 1895. Nazaret now set to paper things so terrible that they can barely be described. His 70-quatrain opus includes the following lines that Bohjalian also recalls in his Newsweek piece:

They killed infidels with axes, daggers, and didn’t ask who you were, whether merchant or coolie...They took the babies out of the wombs of their mothers, and those who witnessed it lost their minds.

|

The oldest photo in the Bohjalian family archives: Nazaret (second right) and his family. The little boy on Nazaret’s lap is Bohjalian’s grandfather.

|

Bohjalian’s grandmother’s father and the Shirinian clan came from Ankara, where they bred horses. One day in 1915 the Ottomans grew tired of paying for the horses, shot her father dead and confiscated the horse farm and family home.

Many a savior

Bohjalian is emphatic in his belief that the stories Armenians have lost are a vital part of the Genocide’s legacy, for they too carry within them our history and our past. When he met his Holiness Aram I, they had an inspiring discussion on how to preserve Armenian culture. “The fact is, we have some of the most beautiful music and cuisine and art in the world. And I think about that a lot at mid-life, recalling my grandmother Haigouhi and my aunt Rose Mary’s amazing Armenian kitchens. I could live on my aunt Rose Mary’s cheese ‘boregs.’ I would also love so much to be back in my grandparents’ living room once more, and listen to my grandfather play his beloved oud,” says Chris.

|

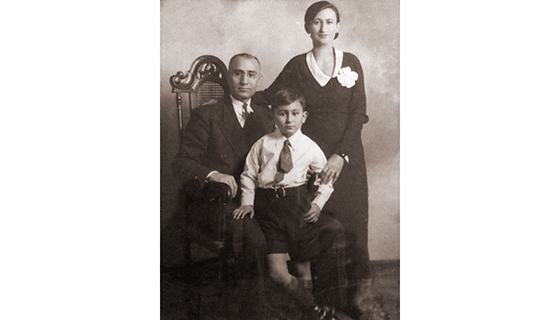

Bohjalian’s grandparents after arriving in the United States, with his father.

|

So in a sense, each person who helped to keep some of these memories alive, from the printer in Kayseri way back in the early 20th century to the local shop people who may have hidden the volume with Nazaret’s poetry within it, or those who may have helped the Bohjalian family to escape with it to America, down to aunt Mary Rose, saved more than simple words or inanimate stories. They saved a part of Armenian life, a family’s past. And it is perhaps completely fitting that some three generations later, another Bohjalian is following in the footsteps of his ancestor Nazaret the Bard rom Kayseri and bringing light to the world through the medium of literature, through a most talented and original wielding of the pen.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.