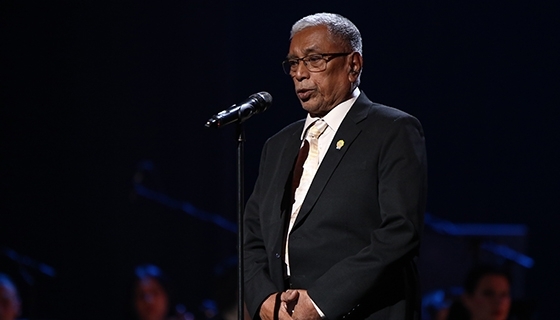

2018 Aurora Prize Laureate Kyaw Hla Aung is a lawyer and Rohingya Leader from Myanmar. Despite being imprisoned for a collective 12 years for peaceful protests against systematic discrimination and violence, he uses his legal expertise to fight for equality, improvements in education and human rights for his community. Here he talks about his struggles and hopes.

Becoming a Lawyer

I was born in Sittwe, the capital of the Rakhine State in Myanmar, on August 16, 1940. I got my education in Sittwe, too. My father was a government official for 40 years, and then so was I. I worked as a stenographer for 22 years, then in 1983 I quit my job because of the increasing discrimination against the Muslim staff. I started working as a lawyer in the Rakhine state instead. I also traveled to other regions for some cases, but mostly I worked in Sittwe.

In 1986 the government started confiscating the lands of the Rohingya Muslim people. They couldn’t get a lawyer to appeal that, so at last they came to me to protect them and to appeal the confiscation of the lands. I wrote an official letter to one of the members of the government who at the time was the Chairman of the National Socialist Party. I went to Yangon to submit this application at the consulate office. After my return to Sittwe I was arrested.

They detained me on August 25, 1986, and I was on trial for two years. Then, on the same day in 1988, there was a big protest, big demonstrations in Yangon. The prison where I was got taken over and the prisoners broke out, but I was locked in a cell and couldn’t get out. A new committee was formed in the aftermath of the protests, and some people came at night and released me from the prison.

Kyaw Hla Aung in Armenia

New Hope

Around the same time, it was announced that anyone can form a political party in Myanmar, because the leaders of the country wanted it to be seen a democratic state. My colleagues in Yangon, some advocates and some friends, invited me to Yangon to join a new political party. We could go freely back then, we could travel freely between Sittwe and Yangon without any restrictions.

We formed a political party named the National Democratic Party for Human Rights and organized our Rohingya community to vote for us. There was a party office in Sittwe, but the headquarters were in Yangon. In Sittwe I was the top candidate to become a member of parliament, and that drew attention of the authorities to me. They conducted some kind of a research to see who could win the election and realized it would most likely be me. So they had me arrested again. They dug up my old case and sent me to the court.

The court with all the generals lasted for just one hour. I was sentenced to 14 years in prison. I was serving my sentence when the 1990 election took place, so without me our party had to nominate another candidate and have the party members vote for him. Some of my colleagues were supporting me in prison by sending my food because prison food was very bad back then. It’s much better now. There was no good rice, no curry, only greens and some vegetables that were not so good. One inmate died in front of me in the hospital because of lack of vitamins.

Kyaw Hla Aung and Héctor Tomás González Castillo in Armenia

Imprisoned for No Reason

If you were a political prisoner, your family couldn’t visit you every day, only twice in a month. My family had it very hard. My daughter graduated from the Sittwe University but was not allowed to go to Yangon. It was very difficult for them to send food and medication to me. I was suffering at the time but luckily one of the prison doctors was my close friend. He had a clinic close to my house. The officials hated him for helping me and transferred him after a few months. But he helped me a lot. Thankfully, there was an amnesty for people who had been sentenced for more than 10 years and had already served many years, so in 1997 I was released. While in prison, I helped other inmates appeal their cases, because some of them were serving 17-20 years sentences.

When I got home, I found out that my house was totally destroyed by some Rakhine people. The police and the military watched our quarter being attacked. 46 houses of Muslim people were destroyed. Many people had to evacuate, including my family. I was at some compound with other people and then the police arrested me again and took me to the station. I didn’t even know at that time where my family was. Thanks to the help from some activists from the international NGOs, including Victoria Hawkins, who is now working with Médecins Sans Frontières in the United Kingdom, I was eventually released, as they drew unwanted public attention to my case.

In 2013 there was a state census. I was sick, but some student threw a stone at the officers and some of them got injured, and the government decided I was somehow involved with that incident and tried to prosecute me. All this was done to make me leave my home country, but I refused to leave my own land. On July 15 they arrested me again. I was jailed again and released again after spending another year in prison. There was another amnesty from the President.

Kyaw Hla Aung at the 2018 Aurora Prize Trilogy

The Shining Light of Knowledge

For many years I have been trying to make sure that our children have access to education. There was an old lady, a doctor, who helped me. She came to the IDP camp because the Buddhist doctors didn’t really care for the Muslim patients. We formed a committee of 33 people whose primary goal was to change the situation with the education. We opened several schools, hired nearly 110 teachers and got more than 10000 students enrolled. There were also tests and everything. But after my last arrest the committee was finished.

When I got out again, I resumed my efforts to give our Rohingya Muslim community, especially its poorest members, access to education and healthcare. Some of the retired people couldn’t collect their pensions, so I had to contact the Rakhine state officials to resolve the issue. There was an old man who knew his money was in the bank, but the bank wouldn’t give it to him. He only got his pension after my intervention. So there was a lot of issues that I had to deal with.

At first there haven’t been so many restrictions. When we formed our political party, we were free to fly to Yangon and organize our people. But when I got out of prison in 1997, I realized that the Rohingya couldn’t move freely from one town to another anymore. That was done by the military. They want to kick out all Muslims from the country, not just from the Rakhine state, but from everywhere. In Yangon there is also a lot of discrimination.

If we don’t have any education, the government can allege that our people are from Bangladesh. If we teach Rohingya the Burmese language, they cannot say they are from Bangladesh. That’s the government’s point. They want to tell the international community that since those people don’t write or speak Burmese, they must be from Bangladesh. But they cannot take me to Bangladesh, I have all the documents confirming that I am from here. If we educate our people, we can improve our country and get our citizenship.

Kyaw Hla Aung in Khor Virap, Armenia

Let the World See

I was very happy when I learned that I was nominated for the Aurora Prize. Armenia is very nice, and the people here are very polite, there is rule and order here. In our country there is no rule and order, and I am very sad for our country. Now the world will accept my words. I always tell journalists when they interview me that they can help us not be exiled from our land, can help the refugees be allowed return to their land. One journalist asked me, “How can these refugees go back to their homes?” I answered, if this refugee says, “this is my land, there is my house”, the government should accept it. It used to be like this and now they are also checking if you are a citizen. They are delaying this, so people can die.

We are not from another land. We are the citizens of this country, Myanmar, but why is this democratic government denying our citizenship? Up to 2010 we could vote, and anyone could get elected. Now no one can vote; no one can get elected. In 1990, our party could nominate a candidate for the parliament election. Why not now? Where’s the logic in that?

We are hoping that the UN and other countries will help us. Otherwise we cannot survive. If the international community does not help us we cannot deal with this, because we cannot trust our government.