John Mirak’s name is well known in Boston, the capital of Massachusetts. A survivor of the Armenian Genocide, he became a successful businessman and earned respect among Armenians both at home and abroad for his commitment to philanthropy. Today, his John Mirak Foundation invests in educational and cultural projects throughout Armenia.

“My father was the epitome of the American Dream. He firmly believed that if you are honest and work hard, you can succeed. He was a role model,” says John's daughter Muriel, who now lives in Germany. Three years ago, Muriel and her husband established the Mirak-Weissbach Foundation, which supports Armenian children and youth in need.

Muriel Mirak is a correspondent for the Armenian Mirror-Spectator and has published several books. Born and raised in New England, she studied English literature at Wellesley College and then became a Fulbright scholar in Italy. She later taught at the University of Milan. “The fact that Italian universities became very politicized in the early 1970s had a strong influence on me,” says Muriel. “I became a political journalist, specializing in the Arab world.” Following operation “Desert Storm” in 1991, she led a humanitarian program in collaboration with the UN called the “Committee to Save the Children in Iraq.”

“We sent Iraqi children to the United States for medical treatment. During a visit home, I showed my mother photos of children injured in the war. Those pictures triggered something deep down inside her, and for the first time in her life she told me the story of how she had survived.

It wasn’t until after my parents’ deaths that my three brothers and I learned the horrific details.

Reading her memoirs was a shock and provoked a kind of identity crisis,” she says. “As a child, I wanted to become integrated, assimilated, American. None of my classmates or teachers knew anything about Armenians, or where Armenia is located. Once a week, I attended Armenian language classes because my parents attached great importance to it.”

|

John and Artemis at their wedding in 1932.

|

A fated match

Muriel’s mother Artemis Yeramian was born in 1914 in Tsack, an Ottoman village near Arabkir. In 1915, the men of the village were executed. The women and children were locked up in a church and then taken to a field to be shot. The bullet missed Artemis. A Turkish shepherd found her and left her on the steps of a mosque.

She was rescued by a compassionate gendarme, who raised her until distant relatives retrieved Artemis after the war and took her to America.

Had the Genocide not occurred, Zaven and Artemis may have met in Arabkir. Zaven was born in 1907 in Mashgerd, near Arabkir. He was eight years old when his father, and then mother and cousins, were executed. Only his ailing grandmother and infant brother were spared. The gendarmes had locked Armenians inside the church for four days. When they were taken to the central square to be shot, Zaven ran home and hid in the barn before taking refuge with a Turkish neighbor. “Approximately a month later I was near the village square with our neighbor,” John wrote years later. “Topal Nury, the chief executioner of the whole region, arrived on horseback, grabbed me and shouted, ‘You were the one that escaped!’ The Turkish woman looked at him and replied, ‘Haven’t you killed enough? Why don’t you leave the boy alone to care for his grandmother, who is dying, and his infant brother?’”

The gendarme let Zaven go and the boy survived.

“Within a week, my grandmother died,” Zaven writes. “I asked the lady’s husband if he would help me bury her… A week later, I went to him again to bury my brother, who was less than a year old and had died from starvation. I was the only Armenian left in the village.”

He lived with Turkish neighbors and worked for them until 1917, when his aunt Anna, looking for the three children she lost on the deportation marches, found Zaven instead. She took him to Arabkir. “The only food we had came from American-sponsored Near East Relief every week. I used to go and get an allowance of wheat for two, and that was enough for the week. The man in charge of Near East Relief was Mr. Knapp. We all thought he was God.” A year later, they joined distant relatives in Aleppo and travelled to the United States in 1921 to reunite with Zaven’s uncle Garabed, who had emigrated ten years earlier.

|

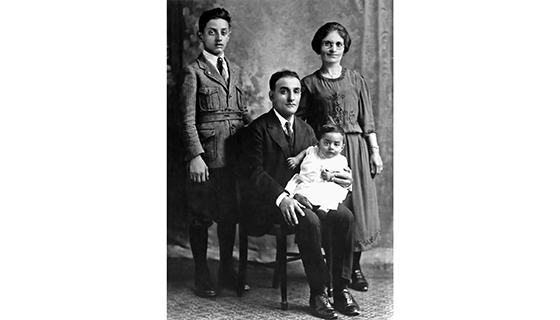

John, his uncle Garabed, his aunt Anna and his cousin Hovsep in the United States in 1923.

|

From selling cars to dealing kindness

In Boston, “Zaven” became “John.” He attended high school, but had to start working at the age of 16. Washing dishes at a hotel in daytime, he learned to be a mechanic at night, and then opened an auto repair shop with three partners. And there he met Artemis, who did the bookkeeping. Married in 1932, they were inseparable until death.

|

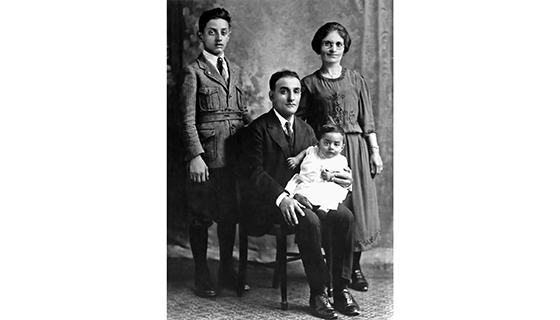

Artemis with her four children in 1943.

|

When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, John was forced to give up the auto shop, but not his belief in success. “My father was very religious. He had absolute trust in God. He would always say, ‘If I survived, it must have been for a reason, and God willing, things will turn for the better,’” Muriel recalls. And that is exactly what happened. Thanks to a supporter, John and his partners set up a new repair shop in Arlington, a suburb of Boston, which later became a franchised Chevrolet dealership that still serves customers at 1125 Massachusetts Avenue to this day.

|

The newly opened showroom of Mirak Chevrolet, 1948.

|

The more he succeeded in business, the more he shifted his focus to charity. “Out of gratitude, wonder, and probably survivor guilt, he felt compelled to repay society through donations and service,” his son Robert writes in “Genocide Survivors, Community Builders: The Family of John and Artemis Mirak.” A historian, Robert studied at Harvard and Oxford, and his doctoral thesis, “Torn between Two Lands: Armenians in America 1890 to World War I,” remains a relevant study to this day.

John made donations to numerous medical, educational, and cultural institutions. As a board member, he offered good counsel to banks like Harvard Trust and Arlington National. He was a fervent supporter of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and funded political campaigns. Boston mayor John Collins and his wife were frequent guests in the Miraks’ home. “Johnny Mirak never forgot his Armenian roots. No reputable charity was overlooked,“ says Robert. He donated to Armenian churches in the United States, the Armenian Tubercular Sanatorium in Lebanon or the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR). In 1978, he won the renowned (Armenian) Ellis Island Award and many other awards from various Armenian organizations.

|

John Mirak and Set Momjian, a one time U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, on Ellis Island in 1978. Both were the recipients of the Ellis Island Award for distinguished community service.

|

Before establishing the private John Mirak Foundation in 1972, John was the dedicated head of the Armenian Cultural Foundation. “Though he had never been to college himself, he truly appreciated education, music and culture. He was determined to preserve everything Armenian,” says Muriel. “He went to his office daily until he was 90. He would come home, sit down in his armchair, take the newspaper, and listen to Armenian music. His death was a great loss for us all,” Muriel mourns. “He was a source of courage and strength for us.” John lived to be 93.

Today, Robert and Muriel honor their father’s legacy by continuing his charitable work. Only recently the Mirak Foundation gave $300,000 to a school in Armenia. “We lost much of our original homeland in the geopolitical game of the Great Powers. To those who demand the return of lost provinces, I say: forget it, it’s an illusion. We have a country, a nation, a sovereign state that needs to be developed. Let’s work together to secure its future and create a lasting prosperity for the young generation,” Muriel says.

The story is verified by the 100 LIVES Research Team.